Challah

In mid-April, around the period of this-stay-in-place-thing-has-already-gone-on-forever-how-much-longer-will-it-last (a lot longer, it turns out), I decided that I needed a way to make different days feel, well, different. Based not on religious practice but on a desire for a ritual to regulate the week, I started to make challah every Friday. For a few short weeks (three weeks, to be exact), while winter still hovered over Chicago, it was a great way to welcome in the weekend.

Over the years I’ve tried a few challah recipes, and this one is easily my favorite. (Hot tip: for anyone in a place where good hamburger rolls are difficult to find, you can make great rolls out of challah dough.) This recipe comes from Tori Avey, whose blog is my go-to for all Jewish foods. When I first made this challah, we discussed making French toast out of it. That never happened, since the challah never lasted long enough to get stale. (Or until Sunday, the day of Big Breakfasts.)

Wheat is the focus for this week. It’s such an integral part of our food system and yet I knew very little about it. Sure, I knew that it grows in the Midwest, like corn and soy, but I didn’t realize that it actually grows in 42 states. And I certainly didn’t realize that there are six types of wheat: hard red winter, hard red spring, soft red winter, soft white, hard white, and durum. Each type grows in different regions, has varying amounts of protein, and therefore is best suited for different uses. For instance, durum is best used for pasta, soft red wheat is generally used for cookies, and hard red spring is often used for bread. While the US produces mainly hard red wheat (according to one estimate, 60 percent of US wheat is hard red), European wheat is generally of the soft variety. For anyone who has had the frustration of using European flour to bake American chocolate chip cookies, the difference in the amount of protein in the wheat, as well as much lower amounts of the mineral selenium in European wheat, helps to explain why baking such simple recipes can go so terribly wrong.

Most wheat is consumed in the same country in which it is grown, although some of the larger producers also export. China produces the most wheat in the world, at 17 percent; India produces 13 percent; and the US, Russia, and France each produce 7 percent of the world’s wheat. In the US, wheat is the third most-grown crop, just after corn and soy. The US exports about half of what we produce. Of the half we keep, we consume about three-quarters of the wheat and only use one-quarter as animal feed. In contrast, in Europe, about half of wheat is used to feed animals.

Global wheat production has tripled since the 1960s. However, the amount of land used to grow wheat has not increased significantly, primarily due to the increased use of pesticides and fertilizers and expanded uses of irrigation. These new technologies have allowed the yield to keep pace with the increasing demand without wheat expanding into more land. Wheat production consumes less water than soy, but it still requires a lot of water – according to one estimate it takes 1,619 liters of water to produce 1 kilogram of wheat. This is in part because it’s grown in such large quantities on large areas of land. This is especially problematic in areas that have high water stress, like China and India. Even in the US, irrigation has used up much of the groundwater in aquifers, like the Ogallala Aquifer, in the Great Plains.

While the use of fertilizers and pesticides on wheat seems to be a problem, information can be hard to find. It seems that farmers rarely use glyphosate – also known as Roundup – on wheat (it’s mainly used for corn, soy, and cotton), but they do use fertilizers that can cause environmental harm. According to Engage the Chain, a website that provides an overview of environmental and social risks for commodities, US wheat producers generally apply nitrate fertilizer to wheat. (According to one statistic from 2009, 80 percent of wheat had nitrate fertilizer applied to it.) Nitrates used to grow wheat (and soy and corn) seep into waterways and every year cause a large dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. This year the dead zone is likely to be about the size of Delaware and Connecticut combined.

Although I don’t believe we can buy our way out of these problems – we need to change regulations, not just purchase organic flour – there are some really great small mills that I (and everyone else) discovered during the sourdough-baking period of Covid. So far I’ve bought flour (including rye flour, spelt, buckwheat, and more) from Maine Mills and Zingerman’s, and I’ve been wanting to try flour from Janie’s Mill, a local mill in Illinois. These mills all ship within the US and the quality of flour is really great, although shipping costs can be high. Additionally, there are a couple of larger companies that are employee-owned and sell good flour. Bob’s Red Mill and King Arthur Flour are both employee-owned, and King Arthur is also a certified Benefit-corporation, or B-corp. A B-corp is a company that focuses on more than on maximizing shareholder profit. It also acknowledges that it must take employees’ and other stakeholders’ well-being into account. While neither of these two larger companies seems to source purely organic wheat, they are making efforts to source more of it. It’s a midway point between Pillsbury and small mills that are pretty expensive.

If you want to learn more about wheat production, take a look at Engage the Chain. And check out this recent article from the New York Times on small grain companies as a path for the US economy.

Challah

Course: Bread, Recipe, Uncategorized8

servings4

hours

Adapted, very slightly, from Tori Avey’s Challah recipe.

You can make one large loaf or two medium sized loaves.

Ingredients

- Challah Dough

1 ½ cups lukewarm water, divided

1 packet active dry yeast (1 packet = 2 ¼ teaspoon or .25 ounce active dry yeast)

1 tsp sugar

1 large egg

3 large egg yolks

1/3 cup honey

2 tablespoons canola oil

2 teaspoons salt

4 ½-6 cups all-purpose or bread flour

- Egg Wash

1 large egg

1 tablespoon cold water

½ teaspoon salt

Directions

- Pour ¼ cup of lukewarm water into a large mixing bowl. Add 1 packet of active dry yeast and 1 teaspoon of sugar to the water and stir gently. Let the yeast activate, about 10 minutes.

- Add the rest of the lukewarm water (another 1¼ cups) to the mixing bowl. Then add the egg, egg yolks, honey, oil, and salt and mix everything together.

- Add the flour to the mixture, a half a cup at a time. When it becomes too hard to mix with a stand mixer, dump it out onto a clean surface and knead it with your hands. I usually get about 3 ½-4 ½ cups mixed into the dough using the stand mixer and then do the last bit of kneading by hand. (If you don’t have a stand mixer, you can still make the dough – you just will have to spend more time and effort kneading the flour in by hand.) The dough will be done when it is smooth and no longer sticky.

- Using about a tablespoon of canola oil, oil a clean mixing bowl. Place the dough in the bowl and move it, flipping it around, until it is coated in oil.

- Boil about 6 cups of water in a medium-sized pot. Take the pot of boiling water and place it on a low rack in the oven. Cover the dough with a kitchen towel and place it in the oven on a rack directly over the pot of water. Let the dough rise for one hour. Be sure not to open the oven door during that time – doing so will let out the steam, which is helping the dough to rise. (Thanks to Tori Avey for this great tip!)

- After one hour, take the dough out of the oven and punch it down several times. Let is rise for another hour, until it has doubled in size again. (I usually put it back in the oven, but any warm spot will do.)

- After another hour, turn the dough out onto a clean surface and punch it down again.

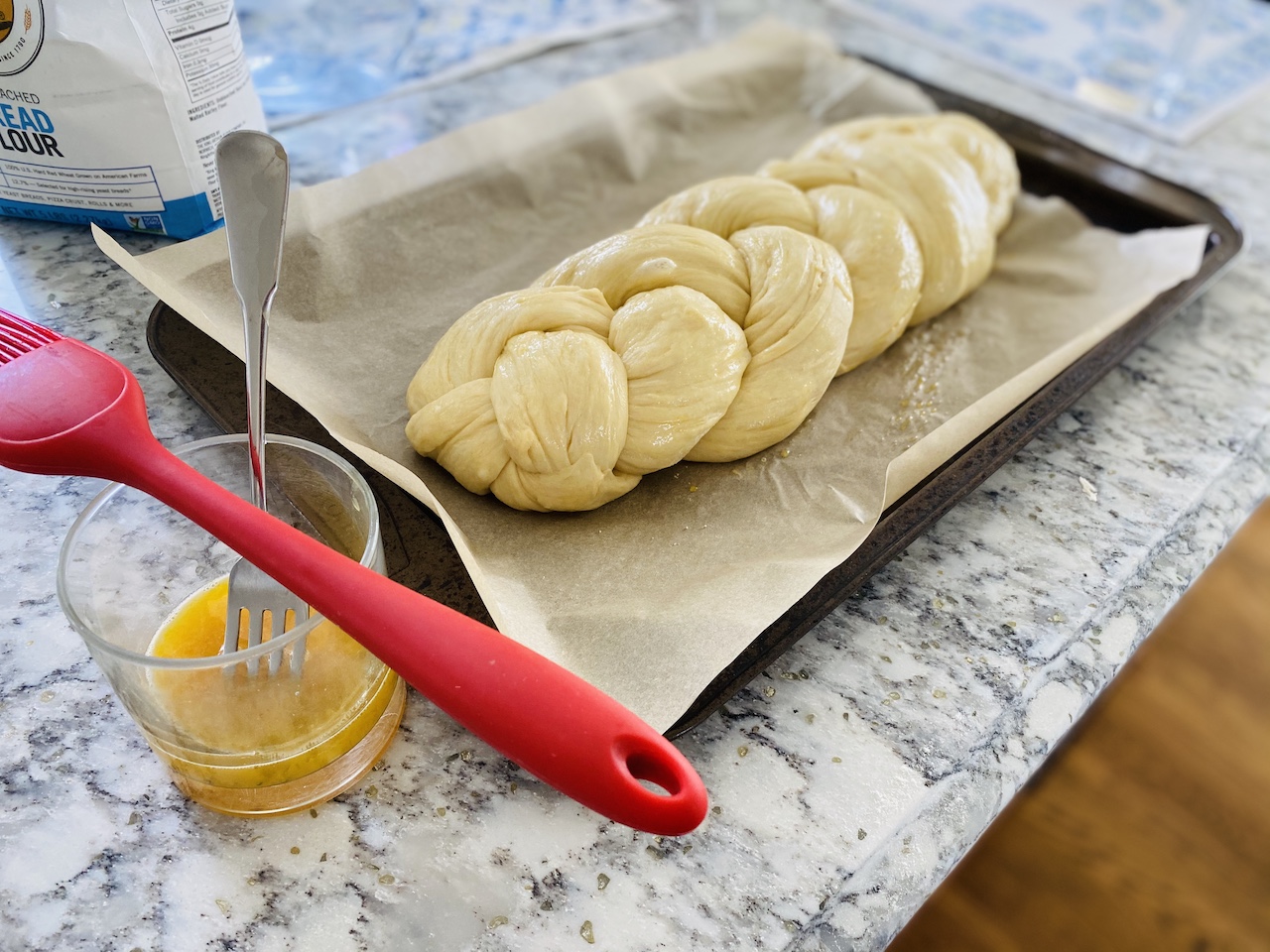

- Now braid your challah. First, line a cookie sheet with parchment paper. Separate the dough into three even pieces and form into long strands, about 15 inches each. Place each strand on the lined cookie sheet. Braid the challah. When I have finished braiding, I like the tuck the ends under the loaf so that it has clean ends.

- Make the egg wash. Mix together the egg, salt, and water.

- Brush the challah with the egg wash. Then let the braided challah rise for 30-45 minutes. The dough is ready when you press it gently and the indentation from your finger remains. (If the indentation disappears right away, it’s not quite ready for baking.)

- Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. You will want to bake the challah for a total of 40 minutes, but in two stages. First, bake the challah for 20 minutes. After 20 minutes, take the challah out and brush it with another thin coat of egg wash. Turn the challah around and put the challah back in the oven. Bake it for another 20 minutes, although keep your eye on it – it might be done a bit sooner, depending on your oven.

- Let it cool for about 30 minutes and then enjoy – plain, with jam or honey, as a sandwich, for Shabbat, or as French toast.

Notes

- Re flour for the challah: I use bread flour when I have it, but I’ve also made it with all-purpose flour and it’s turned out just fine. Bread flour has a higher protein content in it, which means it has more gluten.