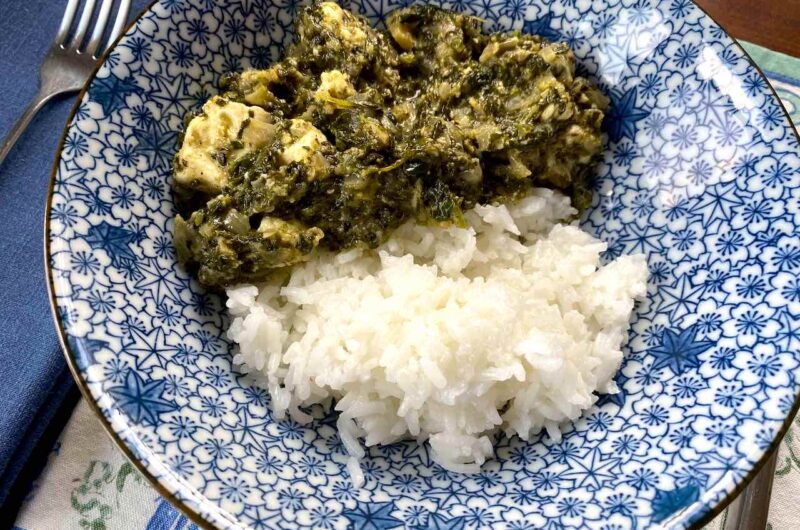

Saag Feta

The pandemic has given me a chance to explore some new cookbooks. There are a few that I’m really excited about, but right now I’m obsessed with Indian(-ish) by Priya Krishna. It’s a collection of “Indian-ish” recipes – think Indian with American influences – that Priya’s mother cooked while Priya was growing up in Dallas. The recipes are simple but tasty, the photos are beautiful, and it has even inspired others in my apartment to try out the recipes. Although I want to cook just about everything in the cookbook, there is one recipe that I have fallen in love with: saag feta. Priya (really, her mother), replaced the paneer with feta and the end result is delicious. The feta melts perfectly into the spinach, adding a saltiness that matches the spice and the spinach.

I could go on and on about the saag, but I’ll get to the point. I’m cheating this week. Instead of an ingredient in the dish, I’m going to discuss an ingredient that goes with (or under) the dish: rice. I recently learned that almost 85 percent of rice consumed in the US is grown domestically and was astounded. Sure, I knew that the US had once grown rice – although the US history I had learned in high school and college was woefully inadequate, I knew that enslaved people had been forced to work the rice paddies in the Carolinas, which was incredibly dangerous and deadly work, where malaria, yellow fever, and other dangers were ever-present. (Also, it was actually enslaved people’s expertise in rice cultivation, brought over from Africa, that made rice growing in the US possible.)

But I didn’t realize that the US was still a major producer of rice. Rice production in the US has become highly mechanized and efficient. Although the amount of land used to produce rice in the US has decreased over the past twenty years, overall production has increased, due to new technologies. Today, the US is the twelfth largest rice producer in the world and the fourth largest exporter. (The US exports about half the rice it produces.) Rice can only be grown in certain warm climates, which is why it’s grown in only six states: Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas. The US mainly produces long-grain rice (about 70 percent of US production), which is primarily produced in the South, while most medium grain rice is grown in California. (Very little short grain rice is grown in the US, accounting for only about 4 percent of all US rice.)

Rice consumption in the US remains relatively low. Americans eat about half a pound of rice per year, compared with people from certain Asian countries, who eat closer to eight pounds per year. However, rice sales have recently increased, especially during the pandemic. While the US produces more rice than is needed for domestic consumption, US rice production is just a drop in the bucket of global rice production. Rice is the fourth largest crop in the world, after sugarcane, corn, and wheat, which means that a lot of rice is produced globally – about 700 million tons each year. About 90 percent of rice is grown in Asia. Globally, rice is a key staple, providing one-fifth of the calories consumed. (Wheat and corn both provide similar amounts of calories globally.)

If you’ve been reading the blog, you may be surprised that I haven’t yet sprung depressing information on you. But don’t worry – here it is. Rice production requires a lot of water and releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. In fact, rice produces double the amount of greenhouse gases that wheat does. According to one estimate, if you eat rice 1-2 times a week for a year, you will have contributed 26 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere (the equivalent of driving your car 66 miles) and used the same amount of water needed to take 202 showers lasting 8 minutes each. (If you have time, play around with this calculator about different food’s carbon footprints. It’s fascinating.)

Most rice is produced by flooding the fields where the rice is grown. This is done to control weeds that would otherwise grow and to make nutrients in the soil available to the plant. However, flooding the rice fields also leads to a high level of methane production, accounting for over 10 percent of all agricultural emissions. Rice produces high levels of methane because the flooded fields stops oxygen “from penetrating the soil, creating ideal conditions for bacteria that emit methane.” More recently some rice farmers have tried to flood their rice fields intermittently, in an attempt to reduce methane emissions. While the current understanding (as well as my understanding of the science behind it) seems a bit tenuous, it appears that fields that are only intermittently flooded may produce as much as 45 times more nitrous oxide than regularly flooded fields. Nitrous oxide is also a greenhouse gas, and, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, may have a “higher climate impact” than methane.

So rice isn’t the environmentally-friendly food that we wish it were. So what? That doesn’t necessarily mean you shouldn’t eat it. For one thing, a lot of people around the world depend on rice for their daily needs and that’s not going to change. But for those of us who are lucky enough to have choices about what we eat and where it comes from, the impact is something to keep in mind. But it’s also important to remember that compared to emissions from beef or other meat, rice is not nearly as bad a choice for the environment.

For a helpful discussion of rice’s environmental impact, take a look at this article.

To learn more about Priya Krishna and Indian(-ish), check out Priya’s website. You can also learn more about why she recently announced that she will no longer be on Bon Appetit’s youtube videos by listening to two podcast episodes by the Sporkful on the turmoil rocking Bon Appetit. (Here are links to both the first and second episodes.)

Saag Feta

Course: Dinner, Recipe4

servings45

minutesAdapted from Priya Krishna’s Spinach and Feta Cooked Like Saag Paneer in Indian(-ish).

Ingredients

¼ cup + 2 tablespoons ghee or olive oil (split up)

1 ½ teaspoons ground coriander (or 2 tablespoons coriander seeds)

2 cardamom pods

1 small yellow onion, diced

1 tablespoon of ginger, roughly chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

1 pound of spinach (or about 10 ounces of baby spinach)

2 teaspoons lime juice

1 serrano chile, roughly chopped

½ teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

½ cup of water

8 ounces feta cheese, cut into ½-inch pieces

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

¼ teaspoon red chile powder

Directions

- Heat the ghee in a large pan over medium heat. Wait until the ghee has melted and then add the coriander seeds and the cardamom pods. Cook over medium heat for about 2 minutes, stirring, until the spices are slightly browned.

- Add the onion to the pot and cook for about another 5 minutes. When the onion is translucent, add the ginger and garlic and cook for 1 minute.

- Add the spinach and cook over medium heat until it has wilted, about 5 minutes. You may need to add it in batches so that it doesn’t overflow.

- Turn off the heat and add the lime juice, green chile, and salt. Stir everything together and then let it sit, with the heat off, for about 5 minutes. It needs to cool for the next step.

- Once the spinach has had a chance to cool, add the mixture into a food processor or a blender. Blend it until it is in small pieces, but not too mushy – it should have some texture but no large chunks. (For a food processor, it takes about 5 pulses to get to the correct consistency.)

- Pour the blended mixture back into the pan and add ½ cup of water. Cook over low heat for 1-2 minutes, until it is gently simmering, and then add the feta cheese. You want to be gentle when stirring in the feta cheese. Try not to let it crumble too much, although depending on the type of feta it may fall apart. Cook for another 5-7 minutes, until the feta has started to melt slightly into the spinach and the water has cooked off.

- While the feta is cooking, warm 2 tablespoons of ghee in a separate small pot over medium heat. When the ghee has melted, add the cumin seeds and cook for 1 minute. After 1 minute (or when the cumin seeds have started to sputter), turn off the heat and add the red chile powder. (Be careful – it’s easy for the cumin seeds to burn.) Stir the red chile powder into the ghee mixture and pour over the spinach.

- Serve over rice and enjoy!